Fairgrove Eichler Neighborhood in Cupertino: A Deep-Research, Vivid Expository Report

Fairgrove is a rare kind of Silicon Valley artifact: a mid-century tract whose design vocabulary is still legible at street speed—low, horizontal rooflines; open yards with spare geometry; and a glass-forward relationship to gardens and courtyards that makes the neighborhood feel simultaneously private and luminous. In official City documentation, Fairgrove is described as a bounded area in southeast Cupertino (Phil Lane north, Tantau Avenue east, Bollinger Road south, Miller Avenue west) and as a coherent group of roughly 220 Eichler homes built in the early 1960s.

The Fairgrove story is also a governance story. The City of Cupertino’s Eichler Design Handbook (Fairgrove) (dated January 16, 2001) states that Fairgrove residents approached the City to preserve neighborhood identity and privacy as growth intensified; a citywide architectural survey supported preservation; and a collaboration among the neighborhood, an architectural consultant, and the City led to the adoption of “R1e – Single Family Eichler” development standards and rezoning of Fairgrove as an R1e district. The handbook emphasizes that its design guidelines are voluntary, focusing on the exterior elements considered essential to neighborhood character, while zoning standards provide enforceable baseline controls.

Architecturally, Fairgrove’s official guidance documents foreground the tract’s “Eichler DNA”: open plans, glazed atriums, radiant-heat floors, slab foundations, and extensive glass, paired with materials and proportions that keep the homes visually quiet—vertical redwood/plywood siding, tongue-and-groove soffits, and simple square-ended beams and posts. In UC Berkeley’s Environmental Design Archives (via an ArchivesSpace record for the Oakland & Imada Collection), Fairgrove appears as “Fairgrove Tract 2533 & 2828 Cupertino CA, 1959–1961,” with Anshen & Allen listed as creator—evidence of the tract’s professional design and documentation pipeline at the time of development.

Culturally, Fairgrove’s community life reads like two overlapping timelines: an early tract era remembered through neighbor recollections (including accounts of block parties when the tract was new), and a present defined by long tenure, high demand, and careful renovation decisions made under the pressure of modern expectations (energy performance, home office needs, kitchen expectations) and the neighborhood’s mid-century constraints. In today’s pricing context, Fairgrove sits inside ZIP 95014, where Redfin reports a January 2026 median sale price around $3.069M and “somewhat competitive” conditions; a 2025 Fairgrove sale example closed at $2.47M (6211 Shadygrove Drive).

Research approach and source notes

This report prioritizes primary and quasi-primary sources tied directly to Fairgrove’s planning, regulation, and archival record: the City of Cupertino’s Eichler Design Handbook (Fairgrove) (2001) and related City planning-area documentation; and an archival description from the UC Berkeley Environmental Design Archives identifying Fairgrove tract materials and dates.

For community texture, it draws on a reported neighborhood feature from the Eichler Network that includes resident recollections about Fairgrove’s early social life. For schools and parks, it uses official pages from the Cupertino Union School District school site and the Fremont Union High School District directory, plus the City’s parks/rentals information for Creekside Park.

For market context, it uses Redfin’s ZIP- and city-level housing market summaries, Zillow’s ZIP-level home value index data, and a sold-listing record that explicitly references Fairgrove and a closed sale price.

Where the user requested specific items that are not fully accessible or not clearly documented in the sources above—especially original 1960–1961 Fairgrove marketing brochures/ads—this report flags details as unspecified rather than inventing certainty. (A brokerage narrative describing original pricing and “phase” distinctions is available and clearly labeled as secondary, not archival.)

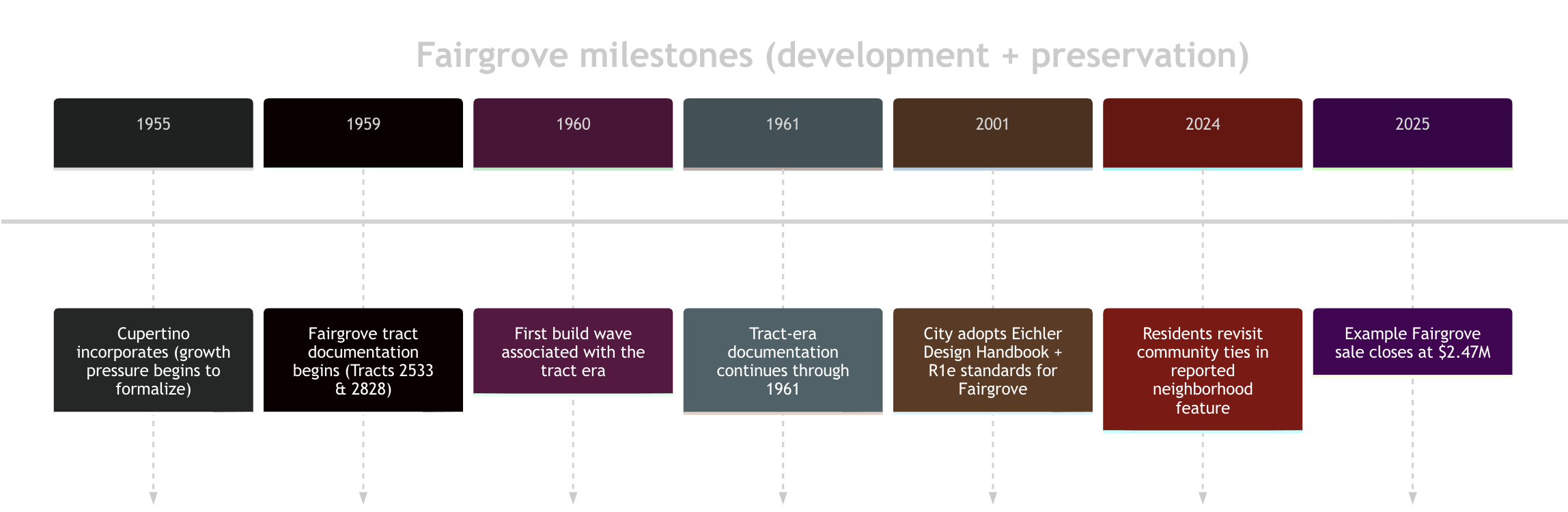

History and development timeline

Fairgrove’s development sits in the larger transformation of Cupertino from orchards to suburb and, eventually, to a global tech address. The Cupertino Historical Society & Museum describes Cupertino’s incorporation era as the start of a rapid building-industry reshaping of the newly incorporated city’s boundaries (incorporated October 10, 1955). The City’s own history narrative places Cupertino’s later identity shift in the broader arc of the “Valley of Heart’s Delight” becoming Silicon Valley, noting the arrival of Apple in 1977 and the later opening of Apple Park.

Against that macro backdrop, Fairgrove’s official neighborhood definition is unusually crisp. In the City’s Eichler handbook, Fairgrove is bounded by Phil Lane, Tantau Avenue, Bollinger Road, and Miller Avenue, and described as a group of 220 Eichler homes from the early 1960s that maintained a consistent Eichler architectural style.

The archival timeline begins slightly earlier than the build date most residents cite. UC Berkeley’s Environmental Design Archives record Fairgrove as “Tract 2533 & 2828 … 1959–1961,” implying pre-construction planning and production drawings in 1959 with development and/or documentation extending through 1961; the same record lists Anshen & Allen as creator.

The “preservation timeline” is formalized in 2001. The City’s handbook states that Fairgrove residents requested help preserving neighborhood identity and privacy, a City architectural survey supported preservation, and collaboration among residents, a consultant, and the City produced R1e development standards and rezoning.

Key timeline anchors above are directly supported in City and archival documentation and a reported neighborhood article.

Architectural features specific to Fairgrove Eichlers

Fairgrove can be “read” as a set of repeating design decisions that favor horizon over height, garden over façade, and light over ornament—a grammar reinforced not by nostalgia alone but by the City’s written guidance on what counts as “Eichler” in Fairgrove.

Form, plan shapes, and indoor–outdoor sequencing

The City’s handbook defines Eichlers broadly as modernist homes built by developer Joseph Eichler, emphasizing indoor–outdoor living via open plans and glazed atriums, plus technical features like radiant-heat floors. While the handbook does not publish a full catalog of Fairgrove model numbers, it does specify that compatible building form and remodel outcomes should stay within simple, geometric plan logic—rectangular and classic Eichler shapes such as “L,” “H,” and “C.”

That plan logic drives a very particular daily choreography—less “front door → hallway” and more “threshold → protected outdoor room → glass-lit interior.” Even the language around second-story additions (discussed because pressure exists) references how second-story walls might align only at the rear of the atrium in an atrium model—implicitly affirming the atrium as the organizing void around which privacy and massing are negotiated.

Rooflines, glass, and materials as an enforced quiet

The Fairgrove handbook’s aesthetic is deliberately restrained: it pushes toward a limited material palette and away from visual “noise.” In its design guidance and zoning matrix summary, it calls out vertical redwood/plywood siding (with specific width ranges), tongue-and-groove soffits, concrete block or brick fireplaces, and simple square-ended wood beams and posts as the desirable baseline.

For glazing, the same summary guidance emphasizes glass on gable ends or tall walls, and specifically discourages grids—an important detail because it explains why Fairgrove’s best-preserved façades feel like calm planes rather than subdivided fenestration. Color guidance similarly steers toward muted earth tones, reserving bright colors for sparse accent moments (often the front door).

Streetscape as architecture: how Fairgrove “reads” from the sidewalk

The handbook’s streetscape guidelines are unusually explicit: Eichler homes “usually have open front yards” with walkways and planting beds laid out in simple geometric patterns, and (in the summarized matrix) no screening is required in the front yard. Read literally, this is a plan for a neighborhood that feels open without feeling exposed: you can see air and planting rhythm from the street, while the home’s real life is pulled inward toward patios, atriums, and rear gardens.

Typical size cues from tract-era parcels

On the ground, Fairgrove’s parcels cluster around a tract-era “family suburban” lot size. Redfin public-record summaries for Fairgrove parcels show lot areas like 6,136 sq ft with a 1960 build year (example: 882 Brookgrove Ln) and tract recording references to “Tract 2533 Fairgrove.” A second example (822 Stendhal Ln) shows 6,500 sq ft and tract references to “Tract 2828 Fairgrove Addn.” These samples support a practical working range of roughly ~6,000 to ~6,500 sq ft for many Fairgrove lots, with variation lot-to-lot.

“Low rooflines and a generous tree canopy amplify Fairgrove’s horizontal feel.”

“The atrium as a ‘protected outdoors’—a signature threshold condition for Eichler living.”

“Post-and-beam rhythm, glass expanses, and the changing light of a temperate-climate house.”

“A close view of vertical grooved siding—material restraint as neighborhood identity.”

Community and cultural life

Schools as neighborhood anchors

Fairgrove’s civic geography is unusually school-centric. The City’s planning-area description notes that Hyde Middle School is located within the Fairgrove neighborhood.

For the elementary-to-high-school arc frequently associated with Fairgrove addresses, the official school and district pages provide concrete anchors: D. J. Sedgwick Elementary School lists its address as 19200 Phil Lane, Cupertino. The district directory for Fremont Union High School District lists **Cupertino High School at 10100 Finch Avenue, Cupertino.

Parks, walks, and the “daylight schedule” of the tract

Just outside Fairgrove’s residential grid, **Creekside Park functions as a practical backyard for the neighborhood’s outdoor rhythm. The City lists Creekside Park’s picnic area address on Miller Avenue and describes the site as including partial shade, a children’s play area, an open grass field, and restrooms—an amenity set that reads like a continuation of Eichler indoor–outdoor living at the municipal scale.

Traditions, neighborly culture, and what changes when a tract becomes “legacy”

A neighborhood’s culture is often best captured not in statistics but in what residents remember was normal. In a reported 2024 feature by Dave Weinstein on the Eichler Network, an early Fairgrove resident, Nancy Burnett, recalls that when Fairgrove was new, block parties played a major role in tying the community together—and that she and her husband bought their home from Eichler Homes even before it was built, a detail that underscores the “buying into a future” psychology of early tract life. The same piece frames a present-tense effort by some neighbors to “reconnect,” suggesting that high-demand stability and long tenure can sometimes thin the casual social fabric that was easier when everyone arrived at once.

Demographics over time: what is known, what is not

Neighborhood-specific demographic time series for Fairgrove (as a tract-within-a-tract) is unspecified in the primary sources reviewed here. What can be stated with evidence is that Cupertino, citywide, has experienced major demographic shifts over recent decades; for example, publicly compiled demographic tables in widely used references report a rise in the Asian share of the population between 2010 and 2020. Any claim more granular than city-level (e.g., Fairgrove-specific ethnicity percentages over time) should be treated as unspecified unless derived from a dedicated census block-group analysis or local survey not accessed in the sources used here.

Preservation and renovation trends

Fairgrove’s preservation posture is unusually formal for a tract neighborhood: it is not only admired; it is documented, narrated, and regulated.

The 2001 inflection point: from “taste” to written standards

The City’s 2001 handbook explicitly documents why the guidelines exist. It states that residents approached the City to preserve neighborhood identity and privacy, that a City architectural survey confirmed preservation value, and that a collaboration (neighborhood + consultant + City) led to adoption of R1e development standards and rezoning as an R1e district.

The same handbook makes a critical distinction: the design guidelines are voluntary, intended to encourage successful design solutions while preserving identity, and to focus only on exterior elements essential to neighborhood character. This matters because it reveals Fairgrove’s preservation strategy as a hybrid: some controls are “soft power” (guidance and neighbor norms) while zoning and development standards create harder edges.

Who “holds” neighborhood integrity?

The credits section of the handbook names both an architectural consultant—Mark Srebnik—and a community group titled the “Fairgrove Neighborhood Eichler Integrity Committee.” The presence of an integrity committee is evidence of organized neighborhood participation in preservation thinking; whether a formal HOA governs Fairgrove is not specified in the City handbook itself and should not be assumed from the committee’s existence alone.

Modernization vs. preservation: the pressure points

The handbook’s content effectively reveals where homeowners feel pressure to change the most: glazing (and its visual grid/no-grid character), material substitutions, color shifts, and especially second-story additions that can create privacy conflicts in a glass-forward neighborhood. Even without a catalog of specific remodel projects, the text makes the design logic clear: protect horizontality; keep materials limited; avoid fussy fenestration; and treat privacy as a central architectural resource rather than an afterthought.

Landmark status

No City-issued landmark designation or National Register listing for Fairgrove itself is stated in the primary City documents cited here; instead, Cupertino’s preservation approach for Fairgrove is articulated through zoning and design guidance. For context, other Eichler districts in the region have pursued formal historic listing paths (for example, Fairglen Additions in San Jose is documented as listed on the National Register of Historic Places).

Real estate context and market evolution

Tract-era physical “givens” that still shape value

Fairgrove’s tract identifiers are not just historical trivia; they are still embedded in modern listing data. Public-record summaries on Redfin explicitly reference “Tract 2533 Fairgrove” (Book 111, Page 36) for multiple properties, while others reference “Tract 2828 Fairgrove Addn” (Book 129, Page 31). Those tract references help explain why Fairgrove feels cohesive: the neighborhood’s coherency is literally recorded.

Lot sizes commonly cluster around ~6,000–6,500 sq ft (examples cited earlier), while living area spans a broad range depending on model and later modification (examples within Fairgrove-related listing data include ~1,272 sq ft at 822 Stendhal Ln, and other Fairgrove addresses exceeding 1,400–1,700+ sq ft). A larger footprint example associated with Tract 2828 appears in Redfin data (658 Stendhal Ln lists 2,339 sq ft total building with 1,499 ground-floor sq ft—indicating configuration/record complexity that owners should verify against permits).

Original pricing: what is and isn’t evidenced here

The City handbook does not publish original 1960–1961 Fairgrove sale prices. A brokerage site narrative states that Fairgrove Eichlers “fetched an original selling price of only $20,000” in the early 1960s and describes the tract as built in two phases (1960 and 1961). This is secondary, and should be treated as suggestive rather than archival unless corroborated by period advertisements or builder brochures.

As wider context (not Fairgrove-specific), a digitized housing document referencing Eichler Homes, Inc. cost facts from the early 1950s indicates the general affordability band Eichler targeted in earlier years, but it is not evidence of Fairgrove’s exact 1960–1961 pricing.

Current price ranges and market signals

Fairgrove sits within ZIP 95014, where Redfin reports a January 2026 median sale price of $3.069M, with homes receiving ~3 offers on average and selling in ~26 days (ZIP-wide, all home types). Zillow’s ZIP-level index reports a typical home value of $3,037,772 as of January 31, 2026 (methodologically different from a median sale price, but directionally consistent in placing the area above $3M).

A Fairgrove-specific closed-sale example (6211 Shadygrove Drive) sold for $2,470,000 on January 2, 2025; the listing language explicitly situates the property in the Fairgrove Eichler neighborhood and ties value to the neighborhood’s architecture and schools.

The sensory economics of the tract

In Fairgrove, “value” is not only square footage math. It’s also the daily experience of light quality and privacy architecture: the absence of fussy street-facing windows; the sense that the house turns its face toward an inner garden; the way mature canopy and low eaves turn midday sun into a softened glow. Those experiences are not easily replicated by new construction—especially in places where second stories become the default response to land cost. The City’s guidelines, by privileging horizontal form, simple materials, and privacy protection, effectively preserve the sensory dividend that makes the tract feel like a calm pocket within a high-intensity region.

Table of Contents

Fairgrove Compared with Other Eichler Neighborhoods in the Region

The purpose of this comparison is not to rank neighborhoods but to clarify what makes Fairgrove distinct: a single-city Eichler enclave with codified guidance, a tract-level archival footprint, and a strong “still-readable” streetscape.

I. Purpose of the Comparison

Why Comparison Matters in Mid-Century Modern Context

Defining “Distinct” vs. “Better”

Methodology and Source Constraints

II. The Fairgrove Baseline – Fairgrove

Geographic Context within Cupertino

Documented Build Era (1959–1961 archival tract record; early 1960s City)

Scale and Cohesion (~220 Homes)

Planning DNA

“L,” “H,” and “C” Plan Families

Glazed Atriums & Courtyard Logic

Radiant Heat Slab Foundations

Vertical Grooved Siding & No-Grid Glazing

Streetscape Legibility (“Still-Readable” Design Language)

Preservation Structure

R1e Zoning Standards

City-Issued Eichler Design Handbook

Named Integrity Committee

III. Fairglen Additions (Willow Glen)

Location within San Jose

Build Era (1959–1961)

Documented Scale (218 Residences)

Architectural Characteristics

Multiple Distinct Plans

Atrium & Courtyard Orientation

Post-and-Beam Structure + Radiant Heat

Preservation Framework

National Register of Historic Places (June 6, 2019)

Comparison to Fairgrove

Federal Recognition vs. City Codification

Urban Context vs. Single-City Enclave

IV. Greenmeadow

Location within Palo Alto

Design Pedigree

Jones & Emmons Planning

Thomas Church Landscape Influence

Community Amenities & Master Planning Identity

NRHP Recognition (Referenced in Sources)

Comparison to Fairgrove

Designer-Forward Identity vs. Plan-Family Legibility

Community Amenity Model vs. Tract-Centered Cohesion

V. San Mateo Highlands

Location within San Mateo

Build Span (1956–1964)

Largest Contiguous Eichler Development Referenced

Hillside & Terraced Planning Associations

Preservation Context (Not Specified in Source Excerpt)

Comparison to Fairgrove

Scale & Topography vs. Single-Tract Urban Clarity

Regional Footprint vs. Codified Municipal Overlay

VI. Comparative Matrix Overview

Build Era Alignment

Scale & Density

Architectural Purity & Streetscape Integrity

Preservation Mechanism (Federal vs. Municipal vs. Not Specified)

Planning Typology (Flat Tract vs. Hillside vs. Amenity-Based Community)

VII. What Makes Fairgrove Distinct

Single-City Enclave Structure

Codified Design Guidance at the Municipal Level

Tract-Level Archival Documentation

“Still-Readable” Streetscape Consistency

Balance of Flexibility & Integrity

VIII. Research Limitations and Future Study

Need for Additional Historic Context Statements

Municipal Design Guidelines Not Yet Reviewed

Deeper Archival Comparison Opportunities

Toward a Fully Standardized, Apples-to-Apples Matrix

A note on limits: comparatives above are constrained to what is explicitly stated in the sources accessed during this research pass; additional neighborhood monographs, historic context statements, and city guidelines would enable a more granular, apples-to-apples matrix than is possible within the evidence cited here.